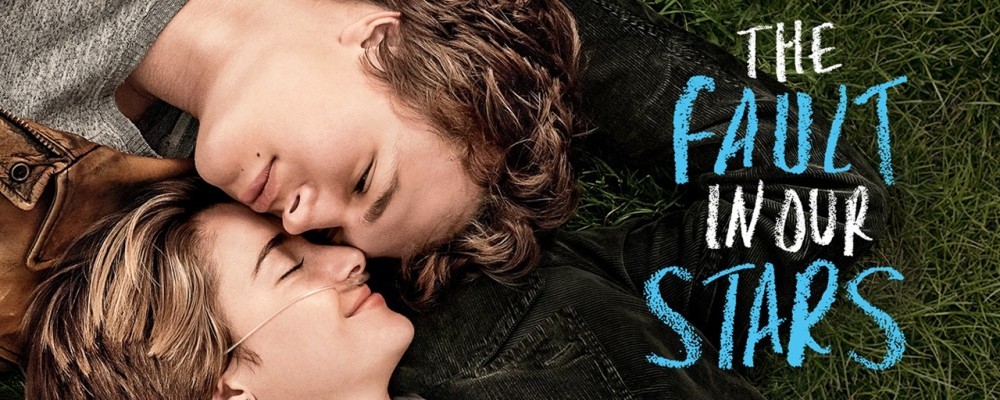

When The Fault in Our Stars came out two and a half years ago, I had no idea I’d one day be sitting down to write about its film adaptation, much less the huge success it would see in the bestseller lists and in high schools across the world. I am happy to say that John Green‘s star-crossed teenage love story has not only done well but has soared, and that this adaptation is faithfully and beautifully done as well.

Now, I am warning you, beyond this point there be SPOILERS. No complaining. And besides, you should’ve read the book already anyway. ~_^

The Fault in Our Stars is the story of Hazel Grace Lancaster (Shailene Woodley) and Augustus Waters (Ansel Elgort), two teenagers facing terminal diagnoses and living their lives despite the impending end. They meet at a cancer support group and bond over their mutual snarky attitudes and realistic view that cancer sucks but life, as it is, must go on. Gus fears oblivion, being forgotten after his death, while Hazel takes a more pragmatic approach to the situation, and soon they are tumbling into a romance that catches Hazel, at least, off guard.

image source: nypost.com

While they bond over a book called An Imperial Affliction, and help their friend Isaac (Nat Wolff) deal with a breakup in the midst of his own cancer battle, Hazel and Gus make a sweet and believable couple; they are given much freedom by parents who probably want more for their children to experience as much of life as possible than to coddle them. Hazel and Gus want answers to what happens after Affliction‘s abrupt end, which sends them on a “Genie Foundation” granted whirlwind quest to Amsterdam. They want to meet the author and live in their infinite present, experiencing romance and freedom in a brief taste of what they can’t have, what life could be.

The one scene omitted from the book version that I particularly missed was the moment when Hazel and her mother arrive to pick up Gus to go to the airport. Hazel hears him fighting loudly with his parents, a screaming match that carries outside. We find out later, of course, that he is insisting that he travel despite his cancer’s resurgence, and that he is now deteriorating. The imperfect interior of their family life mirrors the cancer inside of him: he appears to function well on the outside and doesn’t want to admit his condition, just as the family appears to be happy (with all of those odd affirmations on the walls), the trappings of “normal,” all while dealing with the internal pain of having a family member with cancer. It’s interesting in terms of the character’s story arc, but I can also see why it was trimmed for the sake of time.

image source: nypost.com

Their story is, of course, bittersweet, and the ending builds in a natural way so that we aren’t left mid-sentence with a dark screen. We laugh and cry with Hazel, our narrator, as she faces love and heartbreak just like any young woman would. Her cancer isn’t the point of the story, nor is it her defining characteristic, but more like the oxygen tank she schleps around, always present and slowing her down, but not who she is. Maybe this is a little on the nose, but as John Green constantly reminds us, it is important to imagine things (especially people) complexly, and this is an instance where we step outside of “kid with cancer=CANCER KID” and can see “kid with cancer=KID.”

While the audience is predominantly teens, the film will also play differently depending on your, shall we say, life experience. John Green does such a good job capturing what it’s like to be a teenager, with the world expanding around you, and how it feels to be experiencing things for the first time, and this movie does a nice job of bringing many of his characters’ quirks and metaphors to the screen. Some of the nuance is lost in page-to-screen translation of course (including with some of the dialog: it felt a bit like fan service at points, as if inserted strictly for the quotability despite how cumbersome and awkward it might come across in actual conversation), but much of it remains in tact, and the film is mostly stronger for it. Mainly, though, how you view the story itself will be similar to how you see Romeo and Juliet; Shakespeare’s star-crossed teenagers are often viewed by the young as the embodiment of epic romance, while the older reader sees the tragedy of it. The Fault in Our Stars also walks this line between love and death, weaving the two together in a way so that the audience can experience both.

The real heart of this story is in the forging of relationships, not just romantically, but the connections that we make every day with those around us. Family, friends, even strangers are part of our stories and define us, but also reflect us. A short life can have as much importance as a long one, and sometimes an even greater impact because of the brightness burning in the brevity of it.

To that end, Augustus Waters is remembered not just by Hazel, but by the millions of people who will see his story and be moved by the impression he and Hazel leave. It is a strange thing to carry the life and death of a fictional character inside your head, and yet we all do it. In a way everyone we know is simply the fictional versions of themselves that we create in our minds, adding pieces through conversation, shared experience, time. And in that sense, we live in the little infinities between our neurons, the memories we have of those we encounter in life, be they real or imagined, having lasting impact on us for better or worse. The reach of this story is wide; Augustus, you and Hazel are remembered, and will be for many years to come.

I’ll leave you there, friends; and DFTBA.

*Notes:

1) I attended one of the Night Before Our Stars events, and so was in a theater packed with sobbing and/or wailing fans, which somewhat detracted from the overall experience. If that might bother you, I recommend going to a non-peak-time screening.

2) I’m also aware this sounds a bit like a book review, but the adaptation was so faithful (minus a few scene omissions) that there are bound to be many, many overlaps.

Very insightful review, Joanna! This was similar to my experience during The Night Before Our Stars, as well. The film definitely did not turn into the pandering drivel I was afraid it would become. I can see why John was pleased with it.

Going into the movie, I was really concerned about acting ability (for lack of a better word). Even a few scenes into the film, I wasn’t sure that Shailene and Ansel could really feel like Hazel and Gus to me. But as the movie progressed, they did a fantastic job of embodying the characters (especially during the most difficult scenes, like the middle of the night hospital scare and the gas station scene.) It was realistic and believable and overall I walked away with very little to really complain about.

Just my fannish, nerdfightertastic 2 cents 🙂

Well captured, my friend.

First, it was way fun to tweet with you gals last night amidst the sea of teenagers surrounding us. Not that there’s anything wrong with teenagers, we were all there once…just…so much snot. And so much PDA.

ANYWHO- I like going to these premieres because I like to feel part of the actual human fandom, not just the internet fandom. I do so wish that there was a larger adult population to enjoy it with, but alas, here we are.

I loved it. I do want to see it again without all the wailing, though. One young lady in our theater was sobbing so violently it sounded like she was laughing..at the VERY sad parts..which was…strange. My overwhelming thought was that even without some of the more adult banter between Gus and Hazel in the book, you could HEAR John’s voice on the screen. And I think that is SO important for the younger audience. Young men and women can be smart, witty, empathetic, cynical, and be just as worthy of love as anyone else. No one needs to dumb themselves down in the face of a crush, EVER. I thought Mike Birbiglia as Patrick was PURE MAGIC. If you haven’t watched his stand-up or seen his movie “Sleepwalk With Me”, I HIGHLY suggest you do so immediately. Netflix, BABY. I thought Willem Dafoe as Van Houten was inspired. He has just the right mix of creep factor meets wizened older gentleman. Laura Dern as Hazel’s mom was the most believable for me, and Nat Wolff, I mean, NAT WOLFF. Hilarious and heartbreaking all in one little package.

I’m just so happy they took care of this book. And I’m just so happy to be part of the group that knows how much it meant that they did.

DFTBA, Y’ALL.

Melissa, I had this EXACT experience! A girl sobbing so enthusiastically it sounded like laugher and took me a couple of minutes to pinpoint.

There was PDA at your screening? Holy moly I didn’t see that. But I did see a girl with TFiOS cover-colored hair. I was like, MAD PROPS TO YOU, MADAM.

There was a girl at mine dressed as Hazel, complete with blue rolling suitcase!

Such a great review and it’s pretty spot on with how I felt about the movie. As the movie went on, they really did feel like the Hazel and Gus from the book. And I’m interested to watch it alone as well, as my theatre was also filled with a sobbing audience. Though, during Hazel’s eulogy for Gus, I was apart of that sobbing crowd.

Alas it only comes out in the UK tomorrow. Think I’ll go see it on my lonesome so I can sob into my popcorn! Great review, by the by 🙂

[…] Reviews for June: The month started with The Fault in Our Stars. I thought it was good, and I’d recommend seeing it now that the theater isn’t going to […]

I really enjoyed the film, and I think Joanna’s review is almost spot on what I felt. I only wish they had included the scene where they’re playing video games. So funny.